Robert Mapplethorpe im Guggenheim in New York

Von Caroline Frank

20.06.2013

Unser Reisetipp für New York: Zurzeit beschäftigen sich zwei aufeinanderfolgende Ausstellungen im Guggenheim Museum in New York mit dem Phenomen Robert Mapplethorpe, der 1989 an Aids starb.

Diese Ausstellung mit Schwarz und Weiß Fotografien strotzt vor Leben und Energie.

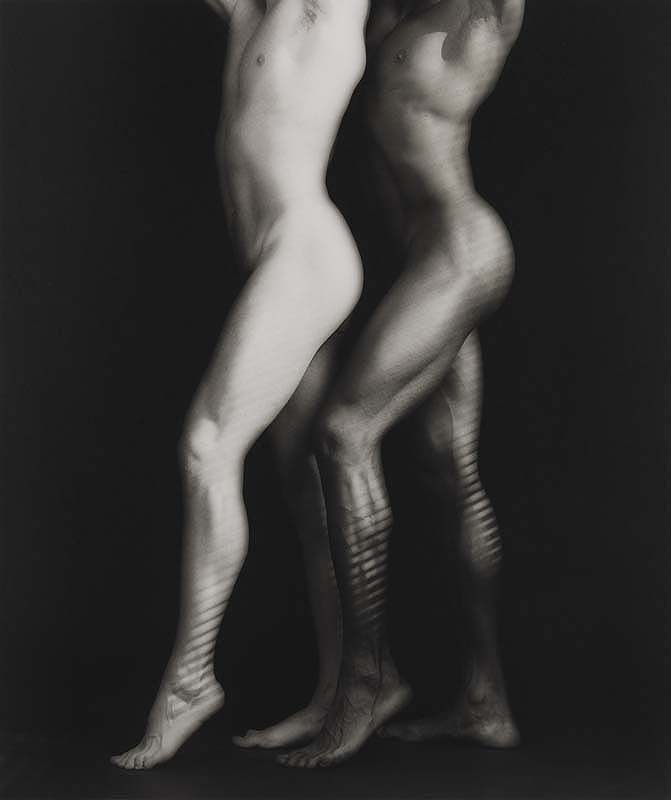

Die Koexistenz eines so breiten Spektrums von Mapplethorpes Fotografien in einem Raum erweckt den Künstler wieder zum Leben. Wir haben die Möglichkeit, in seine Welt der Balance und Perfektion einzutreten. Alle Themen, ob zwei Männer, die sich küssen, ein Selbstporträt, bei dem er als Frau verkleidet ist, wunderbare Blumenaufnahmen oder zwei nackte Körper, haben ihren roten Faden durch die Schönheit von Form, Spannung, Drama und Geometrie der Komposition.

Robert Mapplethorpes Arbeiten sind zweifellos ätherisch.

Selbst das Porträt von Arnold Schwarzenegger in nichts als seinen Unterhosen fühlt sich seltsam an. Aber was genau macht er, um seine Kompositionen so visuell und emotional fesselnd zu machen?

Die schönen Linien, Formen, die ausgewogene Komposition und der Kontrast zwischen Dunkel und Hell sind offensichtlich, aber was macht sie so hypnotisch?

Es ist schwer, einen Finger darauf zu legen, und die beste Erklärung ist die von Mapplethorpe.

Er „erschließt sich irgendwie einen magischen Raum“, wie eine andere Dimension, die irgendwo jenseits der Realität existiert.

In der Ausstellung „Implicit Tensions“ blicken wir durch Mapplethorpes Linse in diese Dimension. Er fängt Schönheit ein, die mit bloßem Auge schwer zu sehen ist. Aber wenn es richtig gerahmt ist, wird deutlich, dass Schönheit in allem zu finden ist.

Portraits und Selbstportraits

Mit nacktem Oberkörper streckt uns der Künstler seinen rechten Arm mit einem schelmischen Grinsen entgegen.

Die sanfte Geste in seiner Hand mit den Sehnenschultern und den Trizepsmuskeln erinnert mich an Michelangelos Erschaffung Adams an der Decke der Sixtinischen Kapelle. Eine sanfte Elektrizität strahlt aus den Augen und Fingerspitzen des jungen Künstlers, der wusste, dass er eines Tages Geschichte schreiben würde. Auf einem Foto in der Nähe blicken zwei Männer kühl nach vorne, gekleidet in schwarzes Leder und Ketten, die sich als dominante und devote Partnerin ausgeben.

Um die Ecke befindet mein bevorzugtes Thema.

Mapplethorpe widmet sich hier der physischen menschlichen Form, ihrer Stärke, Spannung, Haut, Linie.

Das Drama, das vom nackten Körper und dem Kontrast von Licht und Schatten erzeugt wird, ist berauschend. Ich bin fasziniert von einem Foto der Bodybuilderin Lisa Lyon, die nackt mit stolz gebeugtem Bizeps posiert, ein Bein vor dem anderen, der Fuß springt.

Als nächstes eine Reihe von Selbstporträts, von denen einige Mapplethorpe in Perücke und femininem Make-up überziehen, während andere wild maskulin wirken. Er trägt einen bösen Blick und eine schwarze Lederjacke. Das Haar ist auf fettige Weise unordentlich frisiert, und eine Zigarette hängt lose an leicht geöffneten Lippen.

Die Erkundung der Selbstidentität und Selbstdarstellung ist die Beschäftigung des Künstlers mit seiner Identität und Sexualität in den 70er und 80er Jahren in New York City. Dabei scheint er uns Zuschauer aufzufordern, darüber nachzudenken, wie wir unser eigenes inneres Selbst ausdrücken würden. Wie nehmen andere uns wahr? Erkennen die anderen, dass ich, egal wie ich aussehe, immer noch ich bin?

Ein Porträt von Cindy Sherman, Freundin und Kollegin von Mapplethorpe, ist nicht weit entfernt. Auch sie erkundet die Konnektivität zwischen Identität und Erscheinungsbild durch Selbstporträts, in denen sie sich in andere Menschen, Prominente und anonyme Personen verwandelt, die als „sie selbst“ kaum wiederzuerkennen sind.

Eine Reihe von Porträts von Mapplethorpes bekannten Künstlerfreunden schließen sich an, wie z.B. von Louise Bourgeois und Andy Warhol, bei denen die Persönlichkeiten der beiden besonders gut eingefangen wurde.

Die Essenz einer Person in einem einzigen Schnappschuss festzuhalten war eines der Hauptziele von Mapplethorpe in seiner Porträtfotografie.

Sado Maso

Die homosexuellen sadomasochistischen Bilder, viele aus dem illustren X Portfolio, das 1978 veröffentlicht wurde, sind in dem kleinen Raum zusammengefasst, der von den Haupträumen abzweigt.

Die Bilder scheinen ein wenig zur Seite geschoben, vielleicht verborgen wegen des kontroversen Themas. Oder vielleicht würden sie auch den Rest der Ausstellung überlagern, wenn sie im Hauptraum wären.

Die Bilder sind stark, konfrontativ, sogar schockierend. Ich bemerkte, dass einige Leute diesen Abschnitt übersprangen oder nur mit kurzen Blicken schnell vorbeigingen, als ob es ihnen peinlich wäre, die Bilder genau zu studieren, wie sie es für den Rest der Ausstellung taten.

Als liberaler junger Erwachsener, der an der Schwelle der Millennial- und Z-Generationen lebt, ist es für mich vielleicht auch einfacher, ein Porträt eines Mannes zu betrachten, der eine Bullwhip in seinen Anus steckt, oder zwei Männer , von denen einer in den Mund des anderen uriniert.

Dabei soll Kunst auch manchmal unangenehm sein. Diese Erfahrung entlarvt uns, lässt uns mit unseren innewohnenden Charakteren und unseren Gefühlen konfrontieren.

In Mapplethorpes berühmtem Joe (Rubber Man) von 1978 paart der Künstler das Foto mit einem dunklen Spiegel, der sich im selben Rahmen befindet. Schauen Sie sich das Foto an. Und sehen Sie sich dabei selbst im Spiegel.

Blumen

Mapplethorpes Blumenbilder befinden sich, strategisch gut gewählt, gleich neben den Sado-Maso-Bildern.

Die Verwendung von Schwarzweiß und sorgfältigen Winkeln wirkt stark abstrahierend.

Durch die Abstraktion verwandeln sich die Objekte im Auge des Betrachters – und werden schnell sexuell, bis zur Groteske.

Ja, meine Augen und mein Verstand wurden von den sadomasochistischen Bildern angeregt, aber es steht außer Frage, dass diese Blumen fast pornografisch sind.

Verflochtene Stängel sind mit weichem Haar bedeckt, Zwiebel und Staubblätter sind phallisch, Blütenblätter und Blütenstempel sind yonic (Vagina-ähnlich).

Blumen haben Geschlechtsorgane wie Menschen. Warum sind sie Symbole der Schönheit, während Fotos menschlicher Geschlechtsorgane kämpfen müssen, um in eine höhere, schöne Kunst überzugehen?

Mapplethorpe verwischt die Grenzen zwischen Schönheit und Pornografie, Weichheit und Härte.

Fazit:

Robert Mapplethorpe schrieb Fotografie-Geschichte.

Er schrieb Geschichte mit seinen kontroversen Fotografien des nackten menschlichen Körpers, homosexueller Liebe, der Underground-BDSM-Szene in New York und von Blumen.

Er schrieb Geschichte durch seine Darstellung von Form, Figur, Identität, Beziehungen und Sterblichkeit innerhalb dieser Materie. Er hat Geschichte geschrieben, nicht nur, weil er pornografisches Material zur Kunst erhoben hat, sondern weil er alles, was er sah, in Kunst verwandeln konnte. Letztendlich liegt es jedoch in der Verantwortung des Betrachters, etwas als Kunst zu erkennen.

Mapplethorpe gibt uns alle Werkzeuge dafür, aber es liegt an uns, den künstlerischen Wert, die Schönheit und die Magie in diesen Fotografien zu sehen.

„Implizite Spannungen: Mapplethorpe Now“

Die Ausstellung besteht aus zwei Teilen:

Erster Teil: 25. Januar 2019 – 10. Juli 2019, Zweiter Teil: 24. Juli 2019 – 5. Januar 2020

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum und Stiftung

Liberty Plaza

New York, NY 10006

Vereinigte Staaten von Amerika

Mo 10 – 17.30 Uhr, Di 10 – 21 Uhr, Mi – Fr 10 – 17.30 Uhr, Sa 10 – 20 Uhr, So 10 – 17.30 Uhr

Und hier unsere Bilderserie mit 8 Fotos der Ausstellung:

english text

(pictures above)

Robert Mapplethorpe in New York

By Caroline Frank

06/20/2019

Our travel tip to New York: Two consecutive exhibitions at the Guggenheim Museum are currently exploring the phenomenon of Robert Mapplethorpe, who died of AIDS in 1989.

An exhibition in black and white bursts with life and energy. The coexistence of such a wide range of Mapplethorpe’s work in one space brings the artist back to life. We have the opportunity to step into his world of balance and perfection. All of the subject matter, whether it is two men kissing, a self-portrait cross-dressed as a woman, a flower, or two naked bodies, have the common thread of beauty through form, tension, drama, and geometry of composition.

Mapplethorpe’s work is undeniably ethereal.

Even the portrait of Arnold Schwarzenegger in nothing but his knickers feels strangely so. But just what exactly does he do to make his compositions so visually and emotionally arresting?

The beautiful lines, forms, balanced composition and contrast between dark and light are apparent, but what makes them so hypnotic? It’s hard to put your finger on it, and the best explanation is Mapplethorpe’s own.

He just “somehow taps into a space that’s magic,” like another dimension that exists somewhere beyond reality. In Implicit Tensionswe peer into that dimension through Mapplethorpe’s lens. He captures beauty that is hard to see with the naked eye. But when framed just right, using the right perspective and light, shows us that beauty can be found in everything.

Portraits and Self-portraits

The artist invites us in, shirtless, extending his right arm with a mischievous grin. The soft gesture in his hand with sinewy shoulder and triceps muscles reminds me of Michelangelo’s Creation of Adampainted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. A soft electricity radiates from the eyes and fingertips of the young artist who knew that someday he would make history. In a photo nearby, two men gaze forward coolly, dressed in black leather and chains, posing as a dominant and submissive partner.

I turn the corner and approach what will be my favorite section. It is dedicated to the physical human form, its strength, tension, skin, line. The drama created by the naked body and contrasting light and shadow is intoxicating.

I am spellbound by a photograph of bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, posing in the nude with biceps proudly flexed, one leg in front of the other, foot popped.

Next I am drawn to a series of self-portraits, some in which Mapplethorpe cross-dresses, wearing a wig and feminine makeup, others in which appears what would be considered wildly masculine; he dons a bad-boy stare and a black leather moto jacket, hair messily coiffed in a greaser-fashion with a cigarette hanging loosely from slightly parted lips.

This exploration of self-identity and self-presentation provokes thoughts about the artist’s journey with his identity and sexuality during the 70s and 80s in New York City.

It also feels like an invitation to ask us viewers to think about how we outwardly express our inner selves. How do others perceive us? Do they recognize that regardless of how I look, I am still me? Maybe, or perhaps not.

A portrait of Cindy Sherman, friend and colleague of Mapplethorpe’s, is mounted not too far away. She, too, explores the connectivity between identity and appearance through self-portraits in which she transforms into other people, celebrities and anonymous individuals alike, nearly unrecognizable as “herself.”

There are some more portraits of Mapplethorpe’s well-known artist friends, namely Louise Bourgeois and Andy Warhol, in which the sitters’ personalities are impeccably captured. This was one of Mapplethorpe’s main objectives in his portraiture, to capture the essence of a person in a single snapshot.

Sado Maso

The homosexual sadomasochistic images, many from the illustrious X Portfolio published in 1978,are grouped together in the small space that branches off the main rooms.

At first it feels a bit shoved aside, perhaps concealed due to the controversial subject matter. Or maybe they would overpower the rest of the exhibition if they were out front. Perhaps the curators could explain…

The images are strong, confrontational, even shocking.

I noticed some people skip this section or steal quick glances as if embarrassed to study the images closely as they did the rest of the exhibition. As a liberal young-adult living on the cusp of the millennial- and Z- generations, it is easy for me to negatively judge those who might feel uncomfortable looking at a portrait of a man inserting a bullwhip in his anus, or of two men, one of which is urinating into the other’s mouth.

Art is supposed to make us uncomfortable sometimes, though. It exposes us, makes us confront our inherent character and emotions. In Mapplethorpe’s famous Joe (Rubber Man), 1978, the artist pairs the photograph with a dark mirror, juxtaposed within the same frame. Take a look at the photo. Take a look at yourself.

Flowers

Mapplethorpe’s flowers are strategically well placed just next to the sadomasochistic images.

The use of black and white photography and careful angles gives the flower pictures a certain abstraction.

That’s why the plants are transformed in the eye of the beholder – and they are sexual, even grotesque.

Yes, my eyes and mind have been primed by the sadomasochistic images, but there is no question that these flowers are almost pornographic.

Intertwining stems are covered in soft hair, bulbs and stamensare phallic, petals and pistils are yonic (vagina-like).

Flowers have sex organs just as humans do, so why are they symbols of beauty whereas photographs of human sex parts have to fight to transcend into a higher, beautiful, art?

Mapplethorpe blurs the lines between beauty and pornography, softness and hardness.

Conclusion

And so, Mapplethorpe made history as he intended.

He made history with his controversial photographs of the naked human body, of homosexual love, of the underground BDSM scene in New York, and of flowers.

He made history through his presentation of form, figure, identity, relationships and mortality within through that subject matter.

He made history not only because he elevated pornographic material into art, but because he could turn everything he saw into art. Ultimately, though, it is the responsibility of the viewer to recognize something as art. Mapplethorpe gives us all the tools to do so, but it is on us to see the artistic value, the beauty and the magic, in these photographs.

„Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now“

The exhibition goes in two parts: first part: January 25, 2019 – July 10, 2019, second part: July 24, 2019–January 5, 2020

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation

One Liberty Plaza

New York, NY 10006, USA

Mo 10 am – 5.30 pm, Tue 10 am – 9 pm, Wed – Fri 10 am – 5.30 pm, Sat 10 am – 8 pm, Sun 10 am – 5.30 pm

Author: Caroline Frank

Caroline Frank, based in New York City, works at artnet Auctions on the business and sale operations team. She has a passion for fine and performing arts, having studied both art history and dance at Duke University (T’2018).